di GLENDA GARELLI e MARTINA TAZZIOLI

In questo momento è in corso un convegno a Bruxelles su hotspots e relocation, organizzato da policy makers dell’European University Institute insieme a Frontex, Unhcr e varie agenzie, riunite per capire come bloccare i migranti alle frontiere esterne dell’Europa; ed è molto interessante osservare come un incontro sulla migration crisis sia diventato un incontro sull’ammissione della loro stessa crisis, quella di chi i migranti vuole governare. Tutti parlano di un fallimento totale delle loro stesse politiche e piani, a partire da quello della relocation, fino agli hotspots, e più volte è stata usata l’espressione “governance and border crisis more than a refugee crisis” per indicare l’assenza di una strategia europea a lungo termine. Inoltre, la questione della libertà di scelta che i migranti rivendicano e agiscono attraverso il rifiuto a dare le impronte o attraverso proteste collettive come quella degli eritrei a Lampedusa, diventa in questo momento il vero problema a quanto pare di questi policy makers: nella discussione di ieri, il punto centrale è stato cosa fare di fronte al rifiuto dei migranti di essere trasferiti in paesi europei che non possono scegliere,e come questo stia mandando in crisi l’intero sistema. Riprendiamo da www.opendemocracy.net questo intervento di Glenda Garelli e Martina Tazzioli (EN).

The Mediterranean of migrants has taken centre stage in public and political debate. The struggle of people fleeing war and violence saturates the Mediterranean waters and shorelines, as people’s chances to find refuge in a safe country relies on informal crossing routes.

The European “response” to the migration crisis in the Mediterranean, meanwhile, focuses on Italian and Greek islands as hotspots to enforce full identification and border-posts of first deportation, as European Commissioner for Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship, Dimitris Avramopoulos, recently spelled out in an interview.

This third piece in our series on the Mediterranean migration crisis, ‘Transit points and enduring struggles’ takes a look at the Lampedusa hotspot, the first of the 11 hotspots along the Greek and Italian frontline of the EU, which is meant to function as a model for all others. Almost five months into its operation, the Lampedusa hotspot full-fingerprinting policy is mainly resulting in illegalisation and destitution paths for migrants and refugees, as we document below.

The context

Anti-refugee sentiment and politics have spread across Europe in recent months, during which public attention and media coverage of border-deaths and refugees’ struggles at the European borders has been high.

The normalisation of the suspension of Schengen regulations to prevent refugees’ free circulation, the Hungarian barbed-wiring along the border with Croatia to block migrants’ access to its territory, the Swedish deportation schemes to replace those of reception, and the Danish Parliament law allowing the seizure of refugee assets are just a few examples of the expansion of borders, limiting migrant and refugee access to the Schengen area.

At the EU level, the emphasis on providing a ‘response’ to the migration crisis has prompted uncontested warfare interventions, such as the military operation Sophia against smuggler assets; has resulted in a renewed enforcement of the pre-frontiers of Europe, with increased investment in EU neighbouring countries aimed at refugee containment and reception away from Europe; and, has led to lengthy and litigious discussions about the government of refugee access to and presence in the EU.

As migrants keep dying en route to refuge in Europe, the emphasis of the EU conversation about the ‘migration crisis’ has shifted from a humanitarian crisis to a migration management crisis. The focus is increasingly on the so-called “mixed flows” of migrants and refugees reaching Europe and on potential terrorists allegedly embedded among boatpeople.

Under this framing, the governmental imperative becomes screening and identification procedures in order to separate refugees “in clear need of protection” – as EU documents put it – from other figures posited as security threats.

The frontline archipelago – the EU vision

One of the staples of this new EU agenda on migration is represented by the “hotspot approach”, one of the “immediate actions” the European Commission announced in May 2015 to combat the crisis.

Hotspots are infrastructures for intensified interventions by European agencies to support the border functions of member-states in areas of intense migratory flows. In concrete terms, officials of the EU Border Agency (Frontex), the EU Police Cooperation Agency (Europol), the EU Juridical Cooperation Agency (Eurojust), and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) are deployed to the hotspots of Italy and Greece to strengthen these frontline states’ border functions.

Since October 2015 four such hotspots have opened—Lampedusa, Pozzallo, and Trapani in Italy, and Lesbos in Greece[1]—all located in turbulent border “spots” along the Mediterranean frontier of Europe to build a migration frontline archipelago in the central and eastern Mediterranean. The main function of hotspots is the patrolling of migrant bodies and identities: fingerprinting and identifying all incoming migrants, while assigning migratory profiles (economic migrants versus refugees) based on their nationality and on the scanty biographical information gathered during swift identification procedures.

But hotspots also work as enhanced mechanisms of intra-governmental surveillance aimed at ensuring that frontline states, “fulfil their obligations under EU law and swiftly identify, register and fingerprint incoming migrants.”

The various EU agencies deployed as part of the hotspot approach not only offer logistical and technical support for states to perform their border functions, but also act as the watchful eyes ensuring that these frontier states – this soft underbelly of the EU frontier, this Achilles’ heel of the EU borderline, as Greece and Italy are often portrayed – will actually fingerprint all migrants as required by Dublin III regulations.

The hotspot approach was presented in tandem with the EU Relocation Programme[2]: the separation of refugees to protect and migrants to reject binds the hotspot approach to relocation programmes, making humanitarian functions contingent on securitarian ones. Within this framing, hotspots are spatialized as the necessary frontline for international protection programmes, as the filtering border necessary for the humanitarian regime to work.

However, looking at the statistics of the EU Relocation Programme a different scenario emerges, where hotspots actually work to “reject the highest numbers of migrants and accept the smallest number of refugees,” as Mayor Giusi Nicolini of Lampedusa put it. The Mayor has been a vocal opponent of the hotspot approach mandated by the EU for her jurisdiction. The meagre relocation quota for refugees that the Plan envisions provides a quantitative backing for her assessment.

Over a million migrants entered the EU in 2015, coming mainly from war zones and situations of conflict and hence likely to be recognised as refugees at the hotspots. They mainly crossed into the Schengen space through Greece, Italy, and Hungary, hence theoretically qualifying for the EU Relocation Programme, the humanitarian arm of the hotspot approach. In such a context, the EU commitment to relocate a total of 160,000 refugees away from frontline states in the course of two years (2016-17) is, to say the least, quantitatively ridiculous.

Moreover, the Plan’s agonising implementation pace further marginalises the humanitarian component of hotspots: since October 2015 only 279 refugees have been relocated from Italy to other EU member states out of a quota of 39,600; and, only 202 out of 66,400 have been relocated from Greece. As the European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker put it, rebuking the actors involved in the snail-pace relocation programme, at the current pace it would take eight decades to meet the goal.

So not only is the Resettlement Plan for refugees temporary (ending in two years), not only is it highly exclusionary (only the co-nationals of asylum seekers who have at least 75% of recognition EU wide are eligible), it is also an operational flop, as even the EU recognises. Or, to be more precise, it is a fingerprinting plan sansresettlement programme, a vision for full identification without a functioning protection system for those happy few selected to become “resettled” refugees, finally a measure to reject the most and protect the least.

In sum – and at least in the European governmental vision – the hotspot approach serves the implementation of the Dublin regulations on fingerprinting, the regulation requiring the country of first entry to screen and fingerprint third-country nationals and which both Italy and Greece would selectively – though most often would not – apply.

While the talk of the town is about the death of the Dublin regulations and the need to reform them, the hotspot approach is all but intended to overcome them, with EU forces deployed in Italy and Greece to make sure that full fingerprinting is enforced.

The Lampedusa model – illegalization on the spot

But how does the hotspot system actually work on the ground in Lampedusa, beyond official European declarations? Which mechanisms of separation, control, and containment does it enact and what is the impact on migrants’ lives? The hotspot works as a preemptive frontier with the double goal of blocking migrants at the southern borders of Europe and, at the same time, impeding the highest number of refugees possible from claiming asylum.

Italian NGOs and activists have denounced the “nationalist” approach of the hotspot system as a mechanism which separates “economic migrants” from “persons in real need of protection” mainly based on their nationality: people coming from West African countries, for instance, are excluded from protection mechanisms, both from the Relocation Programme and from the possibility of claiming asylum in the country of the hotspot. So they are simultaneously refused protection and illegalised on the spot. Eritreans, Syrians, and Iraqis, who can potentially enter the Relocation Programme are instead allowed to start the asylum procedure.

But what happens to those who are excluded from paths to refuge in Italy or in other European countries? They are officially asked to leave the country within seven days (an expulsion order which is commonly called the “7-day decree”). They are not deported by state authorities; they are issued an expulsion order and asked to pay for their own removal.

So those whom the Lampedusa hotspot does not accept for relocation in Europe or protection in Italy end up remaining on European territory as undocumented migrants, migrants in fact irregularised by the workings of the Lampedusa hotspot.

An explanation for this uncanny outcome of the hyper-securitised outpost of Lampedusa can be found in the economy of humanitarianism: the political and economic cost of managing asylum seekers, refugees, and rejected refugees in a time of economic crisis is clearly higher than the cost arising from a growing population of illegalised migrants, who are in fact a highly exploitable potential workforce and/or are likely to end up leaving Italy for other European countries.

The hotspot of Lampedusa accelerates the exclusion of the highest number of migrants from the hosting and protection system by producing a preventative expulsion from institutional channels of protection rather than enforcing territorial expulsion. The interdependency between the two crises – the economic recession and the so-called “migratory crisis” – has been recentlyrestated at the EU level both discursively and in terms of policy responses adopted by the European Commission: a “border stress test” will be introduced “in parallel to the stress tests in the Banking Union” in order to ensure that “the European Border and Coast Guard have the capacity and means to be ready to face challenges at the external borders.”

Hotspot logistics and operations

Migrants tend to be disembarked on Lampedusa Island as part of Operation Triton, the Frontex-led border enforcement operation, which started in November 2014.

From the small harbour of Lampedusa, they are transferred to the hotspot, which is located in a hollow in the central part of the island. Here the Italian police monitored by Frontex officers perform identification procedures on the spot, both temporally, as immediate identification, and spatially, with a full screening conducted on the island before people get assigned to their different paths and transferred away from Lampedusa.

As part of the identification process, migrants receive an Italian Home Office questionnaire bearing the question, “What is the reason for your being in Italy?” with four options to choose from: “poverty,” “family reunification,” “work,” or “other reasons.” War and persecution are not explicitly listed options and have to fall under the rubric “other,” an odd bureaucratic choice for a form meant to discern refugees from economic migrants.

Migrants we interviewed in Lampedusa in December 2015 and February 2016 and migrant rights associations report that the Italian police ordinarily filled in the document in their place. After the questionnaire step, migrants are held in the hotspot for a variable period of time, usually far beyond the 72 hours established by law, before being transferred to Sicily.

Only once on the ferry that will bring them to Sicily migrants are informed about the outcome of the screening procedure they just underwent on the island, i.e., if they will be taken to a hosting centre on the path to international protection or if they will be given the 7-day decree as “economic migrants.” This is the extent of the governmental procedure.

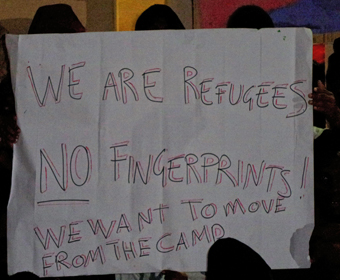

But this procedure often gets jammed when migrants refuse to be fingerprinted, knowing that this procedure implies relinquishing the freedom to decide where to claim asylum in Europe: either as they are forced to claim asylum in Italy – i.e., in their country of first entry – as per Dublin III regulations; or because they are assigned to one of the Relocation Programme countries as decided by officials. By refusing to be fingerprinted, migrants jam the swift screening system of the hotspot frontline and actually end up stuck on the island. A group of 250 migrants, mainly Eritreans, who arrived at Lampedusa on 5 November and 4 December refused to be fingerprinted and organized a protest on 17 December, claiming their right to choose where to seek asylum in Europe.

It is a radical spatial claim laid out by these migrants: it shows how the hotspot system builds upon and contributes to enforcing the Dublin III Regulation, binding migrants’ path to protection to an institutional decision as to where such refuge should be sought.

Fingerprinting has long been a contentious issue between the European Union and Italy as well as between migrants and police officers. A possible “recourse to the use of force” in ensuring migrants’ fingerprinting is indicated in the EU directive released on 15 December.

Yet, as stressed by Fulvio Vassallo Paleologo of the Legal Clinic of Palermo, “recourse to the use of force in fingerprinting procedures has no legal ground.” Italian practices have been aligning with the EU directive for a long time, either with hard measures including beating or with soft measures like “guiding a migrant’s hand” toward the fingerprinting machine or detaining them until they accept to be fingerprinted.

But what are the consequences for refusing to be fingerprinted at the Lampedusa hotspot? Migrants who resist fingerprinting procedures in Lampedusa are caught in a double spatial trap: they don’t enter the protection system and are indefinitely detained on Lampedusa.Migrants who resist fingerprinting procedures in Lampedusa are caught in a double spatial trap: they don’t enter the protection system and are indefinitely detained on Lampedusa, far away not only from their aspired-to refuge, but also from the mainland.

The spatial conundrum (should people give up their freedom to choose where to claim asylum only to end up detained on Lampedusa?) comes from the temporal captivity of indefinite detention on the prison-island. It decelerates the “swift” hotspot approach and results in differential speeds of migration management. Fingerprinted migrants are quickly transferred to hosting centres in Italy, while those who resist identification remain trapped on the island.

In fact, 10 of the 250 migrants who refused to be fingerprinted, are still on Lampedusa after over three months since their arrival, while the others were transported to Sicily, having finally given their fingerprints out of exhaustion or as a result of the use of force.

Collective refusals to be fingerprinted like the one we just referenced should not be regarded only as a disruption of identification procedures, but also as astruggle for a political outcome, i.e. the claim to freedom of choice with respect to where to seek refuge and where to start a new life.

Hotspots are promoted as instruments to identify people “in real need of protection” versus economic migrants. At Lampedusa this logic has so far worked to prevent high numbers of people who have made it to Europe from claiming asylum, has resulted in producing high numbers of illegalised migrants on European territory, and has made refugees the target of suspicion and exclusionary politics.

[1] Four more hotspots will open in the Greek islands of Khios, Samos, Leros, and Kos.

[2] A two-year program for resettling 160,000 refugees arriving in Greece, Hungary, and Italy to other EU countries. Hungary refused both to open hotspots on its territory and to take part in the resettlement program.