di ADOLPH REED.

Riprendiamo dalla rivista Jacobin un’intervista ad Adolph Reed su Bernie Sanders e le elezioni presidenziali negli USA

How do you explain the success of the Sanders campaign? Even if he lost the primary, it is still unprecedented that a self-declared “democratic socialist” almost beat maybe the most powerful politician in the United States. The amount of money Bernie raised, the number of people he brought into the campaign, and the ideas he popularized are quite unexpected.

I think there are several factors that came together to account for the campaign’s success. And I want to underscore the point that it should be seen as a success; it was always a very long-shot possibility that Sanders could win the Democratic nomination, much less be elected president, though ironically perhaps many of us suspected that in some ways he would have been a stronger candidate than Clinton.

Of course, we all had to work as though it was possible for him to win, partly because a very long-shot possibility is still a possibility, and after Iowa the odds didn’t seem quite as long. Besides, otherwise, how could we hope to maximize the campaign’s potential?

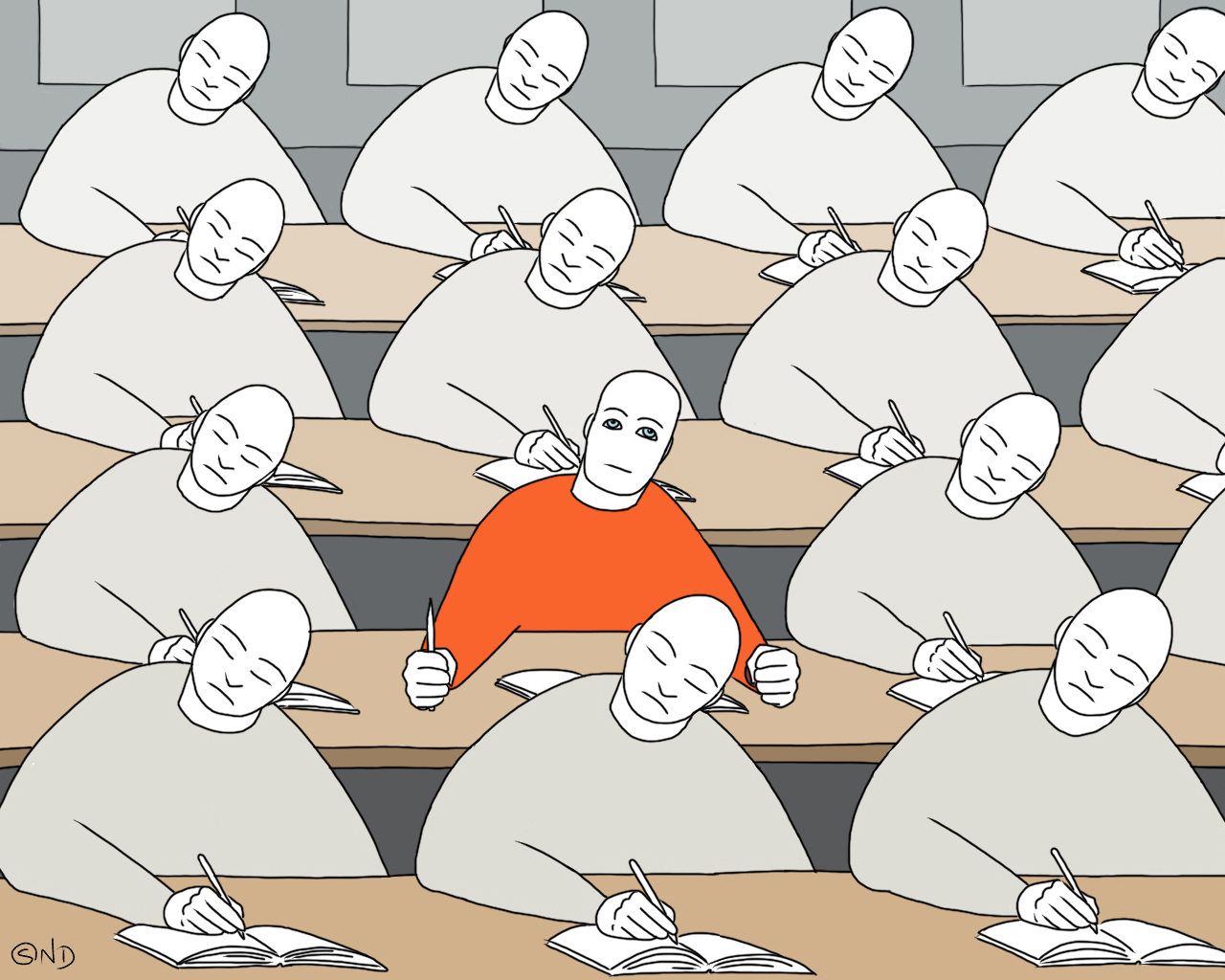

But understandably, some people found it difficult to resist the exuberant optimism that encouraged greater expectations. (A feature of the Left’s position in the United States is that it tends to be stronger on optimism of the will than on pessimism of the intellect.) I often suggested that our model for working in the campaign should be Sgt. Pavlov at Stalingrad: our task was to try to generate as much support as possible wherever we were working at the moment, and it made no difference what opinion polls reported or what seemed to be occurring in other states.

Anyway, I want to stress that point because I’ve recently heard some nominally “progressive” commentators posit the opposite view, that the campaign failed. Some of those expressing it had unreasonable expectations, in part driven by what strikes me as a naiveté about electoral politics, a tendency to underestimate the institutional weight of the party apparatus and its linkages from the local to national levels and through institutional allies like most unions and the civil rights and women’s organizations.

Some who are eager to pronounce the campaign a failure are motivated by other ideological objectives. For example, Trotskyists and others who fetishize association with Democrats as the greatest sin in politics want to argue that Sanders would have been more successful if he’d run as an independent.

That’s a delusional position. In the first place, an independent candidacy outside the Democrat and Republican primaries would have received no attention at all to this point, which means we’d have wasted the last year, and almost none of the unions or other entities would have endorsed it.

Antiracist activists assert or imply that the campaign could have wrested the nomination from Clinton if it had been able to appeal to blacks more effectively, by which they mean if the campaign had given them special standing as ventriloquists of black voters.

The issue of “the black vote” and the Sanders campaign is more complex than what is implied by the construct; there are many black voters whose preferences, concerns, motives, ideological leanings, and institutional connections vary. I know we’ll discuss this later, but the going formulations of the apparent anomaly that Sanders didn’t win a higher percentage of black voters are themselves misguided.

Apart from those critics, other neoliberal Democrats and the commentariat have painted the campaign as quixotic from the beginning and consistently tried to trivialize Sanders and his base. That was only to be expected.

One of the contradictions in trying to use a national election campaign as an instrument of movement-building is that such an effort depends on the broad and immediate visibility that the corporate newsfotainment industry provides. But it’s foolish to expect a fair hearing and assessment from that quarter.

To some extent the campaign tapped into a general frustration in the electorate, a sense that neither regular Democrats nor Republicans address people’s concerns and anxieties.

It would be a mistake to consider all, or even most, of those supporters to be committed leftists or even people embracing sophisticated left critiques of neoliberalism. Many of them are people who are hurting and anxious economically. Motives for supporting the Sanders campaign were various, and, although I think skepticism about parties’ fealty to Wall Street certainly has been a central thread in Sanders’s support, it would be a mistake to try to ventriloquize that broad electorate.

I think the significance of supporters’ acceptance of the “democratic socialism” label is also very much exaggerated. Chatter about it reminds me of the banter that Occupy’s big success was having the New York Times write about inequality. For two decades or more, it has not made sense to think that the term “socialism,” however modified, carries any particular or coherent meaning or range of meanings for the vast majority of Americans.

I understand why Sanders invoked it as much as he did. It was a label already attached to him, and it was reasonable to assert control of discussion of it as an issue by introducing it himself. His adducing of Denmark to explain it or pacify anxieties about it early on seemed a little wonkish and politically ineffective to me, but I could appreciate why he’d do that as well.

However, enthusiasm for seeing the phrase appear in public discourse, I fear, is a testament to the Left’s marginality and capacities for wish-fulfillment and the dominance, even within the nominal left, of the conceptually thin, soundbite-driven premises of mainstream political discourse. I suppose this is what happens when even the Left embraces “branding.”

For the same reasons I never took to the gimmick phrase “political revolution.” I’ve had too many encounters, even in the campaign, with people who imagined that it has more concrete meaning than it does; it’s obviously effective as political rhetoric, but that is because it’s a condensation symbol that means quite different things to different people, and probably nothing really concrete or programmatically specific to most.

We do know that Sanders’s calls for free public higher education and national health care, as well as public investment and financial sector regulation resonated widely. The key issue is how we proceed going forward.

The campaign has large lists of potential activists who can be the base for subsequent, longer-term organizing, and there are multiple discussions occurring among the campaign’s inner circles and its close activist support base, e.g., the Labor for Bernie initiative, about next steps.

Some say that we have to understand Sanders’s defeat as a result of his lack of interest in racism and sexism. Angela Davis wrote that Sanders was a candidate who was “reluctant to address racism” and who engaged in “a kind of economic reductionism that prevents him … from developing a vocabulary that allows him to speak in ways that enlighten us about the persistence of racism, racist violence, state violence.” Paul Krugman argued that he was unable to address “horizontal inequality” and therefore to win the “minority” vote.

What do you think of those critics?

In a way it’s difficult to respond to such charges because they have no concrete content. All through the campaign I asked how a federal minimum wage of fifteen dollars an hour (the current minimum wage is $7.25) is not an issue pertinent to black Americans and Latinos, who are disproportionately likely to be low-wage workers? How decommodified national health care is not a “black issue”? Or free public higher education? Or massively increased public investment? Or renegotiating existing “trade” agreements and blocking the Trans Pacific Partnership, which would further strengthen corporate power against all working people? And so on. No one has argued that black, or other nonwhite, Americans indeed would not benefit disproportionately from implementation of those items of Sanders’s platform.

By contrast, what does it mean to “address racism”? No one in American politics with any aspirations to respectability openly embraces racism — not even Donald Trump. In fact, everyone, even Trump, insists that he or she opposes it.

How is it “economic reductionism” to campaign on a program that seeks to unite the broad working class around concerns shared throughout the class across race, gender, and other lines? Ironically, in American politics now we have a Left for which any reference to political economy can be castigated as “economic reductionism.”

There is moreover no evidence that Sanders was reluctant to acknowledge or discuss racial or gender inequality. What would it mean “to enlighten us about the persistence of racism, etc.”? Surely, Angela doesn’t need to be enlightened; she’s written books on the topic. This line of criticism is either misguided or dishonest.

It is similarly instructive that a strain of identitarian feminists repeatedly sought to characterize support for Sanders as coming mainly from sexist men on the Left. This was an adaptation of an earlier hoax about the existence of a phalanx of misogynist “brocialist” men who threatened feminists with rape or other violence for their reluctance to subordinate feminist concerns to a male-centered class-reductionist socialism.

It’s immensely revealing, and exposing this is one contribution the campaign made that I never anticipated, that we now have a “left” in the United States for which socialism is considered a marker of backwardness. It’s good that that is now clear; it’s always good to know where people stand in relation to class struggle.

I found Krugman’s claim especially interesting, as I did Clinton’s complaint that breaking up the big banks wouldn’t end racism or sexism. It wouldn’t end solar storms or help Bahrain win the World Cup either. Krugman follows a familiar line in the constitution of postwar liberalism that disconnects the idea of inequality from political economy and renders it exclusively as group disparity.

That was really the most meaningful, yet still not often recognized, move Daniel Patrick Moynihan made in his scurrilous 1965 The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, commonly known as the Moynihan Report. Such liberals began trying to make the massive public interventions of the New Deal invisible as early as the late 1940s.

Oscar Handlin, the foremost historian of American ethnicity of his era — we might say he invented the field, which is also telling — laid out an account of ethnic group mobility in 1949 that didn’t mention the New Deal or CIO industrial unionism, which were still vital and dynamic at that moment.

It is especially outrageous now as economic inequality has risen to epic levels that Krugman et al would dismiss it and insist that the object of our concern should be instead how the massive and growing inequality is apportioned among various groups, or population categories reified as groups.

These responses to Sanders’s critique throw into bolder relief just how fundamentally antiracism and other identitarian programs are not only the left wing of neoliberalism but active agencies in its imposition of a notion of the boundaries of the politically thinkable — sort of neoliberalism’s intellectual and cultural border guard.

But don’t you think that, to a certain extent, his campaign was not an antiracist campaign? It is true that he concentrated his message on socio-economic issues. A lot of people within the Left say that this explains part of his failure in the primary to win the support of the black community in Southern states. People called it a “white agenda,” which I found disturbing — Ta-Nehisi Coates even said it will reinforce “white supremacy.”

How can we explain this, and the incredible level of support for Clinton?

We have to understand that electoral politics operates off a particular partisan logic. Cedric Johnson’s essay Fear and Pandering in the Palmetto State is without question the best analysis of the phenomenon of Clinton’s relative success with black voters.

Much of it had to do with the fact that Clinton had the deep relationships with the elite networks that actually turn out voters. There were several other reasons as well. Among Cedric’s important points is arguing against trying to treat black voters as a “black vote” that all thinks with one mind.

We’ve also had thirty years or more of steadily lowered expectations for what can be expected from voting. This was exemplified clearly in South Carolina when longtime Georgia congressman and former Civil Rights Movement icon John Lewis and his fellow black Congressman James Clyburn from South Carolina denounced the Sanders proposal for free public higher education as irresponsible because it sent the bad message that people should expect free things — that is, decommodified public goods and services — from government. “Nothing is free in America,” Lewis snarled.

Sanders did close the gap as the campaign moved along and out of the South. Still, I wouldn’t take the vote for Clinton as an indication that black voters by and large are more committed to an antiracist politics and its agenda than they are to improving their material conditions and security.

That’s the story that the Black Lives Matter and other such activists would ventriloquize from black voters. But it’s their propagandistic invention, particularly as they have no real base among black people who vote anyway. As to the limitations of Coates’s arguments, I strongly recommend Cedric Johnson’s critical discussion in “An Open Letter to Ta-Nehisi Coates and the Liberals Who Love Him.”

What seemed interesting to me was the ability of Sanders to connect his campaign with the broader labor movements in the United States. From the fifteen-dollar minimum wage to his support of the Verizon strike, he seemed always very concerned with creating a positive dynamic between labor activists and his campaign.

Is this the strategy we should consider for the future of the US left?

Yes. I think it’s axiomatic that in the United States, as elsewhere, that, if there’s no firm grounding in the labor movement, there’s no really serious left. A lot of people don’t like to hear that, but I think those are mainly people who prefer their emotionally fulfilling fantasies to pursuit of political power as an objective for building socialism.

It seems to me, in the end, that the really neoliberal candidate is Clinton and not Trump. In many ways both Bernie and Trump voters voted against everything Clinton stands for. On Bernie’s side, against free trade, equal opportunity rather than equality, free markets, an aggressive foreign policy, a pro-Wall Street position were central issues of contention… But on the other side Trump, in his very demagogic way, did also express himself against the free trade deals, Clinton’s foreign policy and, also, immigration as a threat to wages and jobs.

So to a certain extent this debate is not only about “Democrats” vs “Republicans” but also about neoliberalism and its effects. It seems that in the Western world, we are seeing emerging, within the Right, a more extreme narrative that is designed to win the support of the “losers” of globalization.

And in this situation, it is disturbing that the Left seems unable to give another answer than just accusing the “white working class” of being racist. From that perspective, Bernie seems like a sign of hope and the beginning of a perspective for a Left that could unite the working class beyond all this identity politics.

Clinton is definitely the neoliberal candidate. I’m not sure what I’d say Trump is besides an utter sociopath and opportunist who is all too readily prepared to curry favor with the most dangerous tendencies in American politics. I agree with your view of how Trump fits with the right-wing populist politics that’s emerged in Europe as well as here.

It’s also important to recall that the median income of a Trump voter last I saw, which was a couple of months ago, is over $77,000 per annum. That’s not the working class; that’s the small business or petty professional types who are trying desperately to assert or maintain their sense of membership in the respectable strata, those who see themselves as the “real” Americans, identify with the wealthy, and fear encroachment from the working class and especially the nonwhite elements of the working class.

It’s the same stratum of “gentlemen of property and standing” that gave us anti-abolitionist mobs in the antebellum United States, the biggest and most politically powerful version of the Ku Klux Klan as a national phenomenon in the 1920s, the NSDAP, and all other fascist and authoritarian movements.

I agree as well about the hope the Sanders campaign embodied. The campaign showed that it is possible to connect with the broad working class, and I have become increasingly conscious of the extent to which we, including leftists, permit the other side to define the boundaries of the working class for us.

As Nelson Lichtenstein argues, reactionary labor-law reform after World War II — in particular the Taft-Hartley Act, which amended the New Deal–era National Labor Relations Act that had spurred unionization since the mid-1930s — severely restricted the categories of workers eligible for unionization, managing to exclude many so-called “white-collar” and functionary workers.

Of course, as you know, much ink has been spilled in generating exceptionalist accounts of why the United States never developed a system of public social protection as extensive as most of Europe. However, the explanation of the difference can be very simple; after the war the bourgeois classes in much of Europe were weakened and discredited by their association with fascism. Our bourgeoisie came out of the war more powerful than ever and politically rehabilitated through their participation in the war effort.

In any event, everything now hinges on how we can build on the momentum the campaign generated, deepen and broaden contacts in unions, workplaces, communities, campuses — recognizing that the pace is going to be slow, probably decades, as we should see ourselves now really as at the beginning of a long organizing drive.

One of our concerns is, or should be, the tendency among a strain of exuberant leftists to proclaim programmatically diffuse coalitions and subordinate the class program to counter-solidaristic identity politics.

I think we should build on the more visionary aspects of the program, e.g., the demand for free public higher education, decommodified health care, etc and the vital fight to stop the TPP, and yes of course against discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, etc and also against neoliberal policing and the constantly expanding public/private carceral apparatus, which we have to understand and insist that others also understand is a class issue.

How do you think that this campaign can have effects beyond the election? I mean, even Bernie said many times that what he wanted to achieve can’t be done by the president alone (even if it’s him). So his campaign was also about building a political movement that could change the political landscape in the United States.

Do you see a future for Bernie? And what is the place for labor organizations in this process?

In my view everything up to this point was preparation. In that sense the campaign was about showing that open discussion of working-class concerns and programs would resonate and about locating serious activists, organizers, bringing them together, and getting ready to start organizing and mobilizing around issue campaigns and perhaps the occasional electoral candidacy.

That’s another hurdle the Left in this country needs to overcome, the knee-jerk tendency to look for a candidate for office or a neat piece of legislation. Both those should arise from the movement as expressions of its strength; despite the beliefs of those in thrall to the Fourth International and other fantasists, they are not vehicles for generating that strength.

Finally, are you optimistic for the future of the US labor movement?

I have to be. We can’t go anywhere without a vibrant labor movement, and, as longtime Canadian Auto Workers official Sam Gindin and other comrades in the trade unions argue, the labor movement needs a vibrant left as well. That is clearer all the time.

There are many positive signs within the labor movement; the Labor for Bernie initiative was one of the most solid in the campaign and has provided a context for much of the labor left — including many of my old Labor Party comrades — to come together and think strategically in concert.

Even apart from the campaign, there are substantial forces in several unions that are led by progressives and leftists who are committed to the union’s role in broader social-movement building.

It’s a long, slow process, and it will be important for us as militants to keep that in mind. That painstaking approach to organizing is another specialty of the labor movement, the pattern of broadening then consolidating then broadening some more.

I can’t say that I’m confident that we’ll win eventually; the odds are always very long against us, and, as the difficulties our comrades in Brazil and Venezuela are facing from venal bourgeois classes who fear that they can’t wrest control of the society democratically any longer, make clear, the more successful we are, the more perilous the political situation is likely to become.

The difference between Marxists today and those before us is that, except for the glassy-eyed sectarian religionists, we no longer have the solace of teleological confidence. There is no millenarian moment, no objective moment of the crash. We don’t know which ways history will go; we can only try to influence it.

Increasingly these days, as I said in my opening comment, I think Sgt. Pavlov is in some ways a good model for our practice. We don’t need to follow and debate the daily horserace handicapping that passes for news; nor do we need to strive to be the cleverest commentator on the blogosphere — the first to identify the latest “sellout” or the Next Big Thing, the newest trendy source of transformative agency.

Rather, the task is to struggle where we are engaged and hold to it with an understanding that we’re small cogs in a big undertaking and that our efforts should be directed to making it bigger and stronger.

A sports metaphor may be useful in this regard; our job is to put the ball in play and to try to be prepared to react effectively to the often unpredictable conditions that ensue. That, of course, also requires understanding the logic of the game and the nature, strengths and limitations of our opposition as well as our allies.