di MICHAEL HARDT.

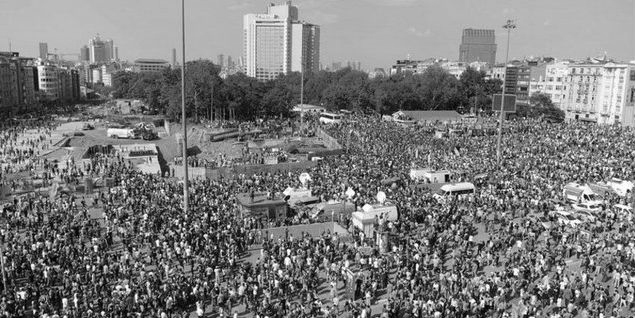

The first anniversary of the Gezi Park encampment will surely be celebrated with joyful demonstrations, which will be met with brutal police repression. One year after they exploded on the scene the movements in Istanbul remain dynamic, combative, and creative. I recognized clearly and immediately the high-level of political and theoretical reflection in discussions with Turkish activists individually and in forums during a two-week residency at Boğaziçi University in May 2014. The taste for political innovation and organizing, as well as a deep antagonism to the ruling powers, is intense. New political habits – such as their distinctive character of the Turkish forums as a practice of collective political reasoning – have been reinforced and socially consolidated. Mixed with inevitable exhaustion and frustration of those who continue to fight, one can see clearly the desire and potential of a movement that points toward the future. Particularly significant for me were discussions in a forum at the Don Kişot occupied social center in the Kadıköy neighborhood, another forum with students at Boğaziçi University, and exchanges with the Otonom collective.

From these encounters I came to understand two primary obstacles that stand in the way of the movement regaining its previous energy and leaping to the next level. (I ask pardon in advance to Turkish comrades for the inevitable errors, omissions, and simplifications in what follows.) First, the movements have not been able to take control of the political agenda and the rhythms of its developments, reacting instead to the government’s actions and to external events. Second, the movements have not yet been able to expand their social composition sufficiently to attain a majority social position. These two obstacles, of course, are closely related, and advancing significantly on the second may be the only way to address the first. For the sake of clarity, though, I will treat the two issues in turn.

1. Stumbling From One Outrage to Another

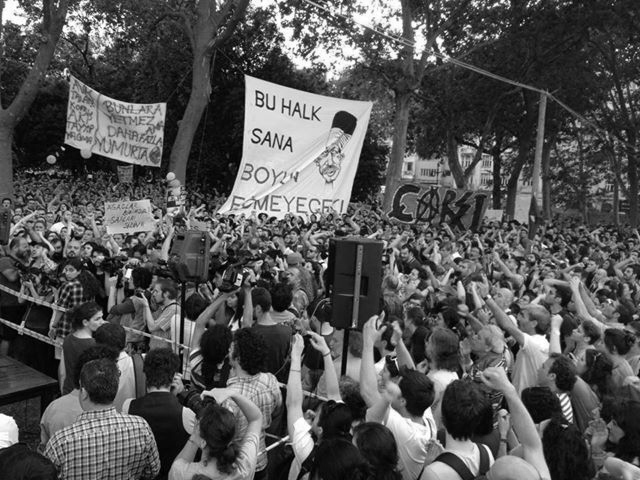

It sometimes seems that the so-called “Gezi spirit” is condemned to stumble from one outrage to another. I arrived in Istanbul in mid May, just in time for the protests that followed the mining disaster in Soma, where over three hundred miners were killed. Little over a week later Istanbul police shot with live rounds at protestors in the Okmeydanı neighborhood of Istanbul and killed a young man, setting off new protests. The demonstrations for the Gezi anniversary are sure to be met with police violence, igniting even more protests.

The actions of the government and the police are indeed outrageous. Every demonstration in Istanbul is met immediately with tear gas, water cannons (containing unknown chemicals), and police violence. I had not understood previously that almost all those protestors killed by the police in this period have been Alevi (not to be confused with the Alewites), and the recent killing in Okmeydanı, an Alevi neighborhood, is no exception. The Alevi, who probably compose between 20 and 30% of the population, are a Shi’ite minority who generally oppose the ruling AKP party, which is supported by the Sunni majority.

The deaths of miners in Soma is a much more significant event with complex implications. Protestors insist on calling it not an accident but workplace murder. Indeed the conditions for the disaster were created by a script, also well known in other parts of the world, that brings together neoliberalism and extractivism. Privatization, subcontracting, and lack of regulation create a situation of dangerous work conditions and little direct government responsibility.

To such atrocities and provocations, the government – and Prime Minister Erdoğan himself – continually adds outrageous words. Instead of offering apologies (or even condolences) to the people of Soma, for instance, Erdoğan was shown on film sparring with angry citizens. This fits with a pattern, at least since Gezi, in which Erdoğan, rather than seeking to accommodate or coopt elements of the protests, demonizes all his opponents, insults them often in boorish terms, and authorizes disproportionate force against them. Machiavelli might advise him that such a rigid mode of governance is fragile – and sooner or later I do think that Erdoğan’s divisive, inflexible, and combative stance will lead to his own political ruin. In the meantime, however, we should recognize how his repertoire resembles that of many other right-wing populist figures whose behavior, although seen as shocking and contemptible by the Left (and indeed any reasonable observer), often serves to solidify the political base. Passionate, outrageous, crude, and offensive outbursts against opponents are standard elements of this repertoire that serve, in the logic of right-wing populism, to demonstrate solidarity with “the people” against the cultural élites.

Erdoğan certainly does his best to personalize and center on his figure all of Turkish political life. A strategy that unites the Left, however, by correspondingly focusing its antagonisms on the Prime Minister seems to me limited and weak. Hatred of Erdoğan among activists is, of course, widespread and deep. Even if the protests were “successful” and Erdoğan were deposed, though, that is no guarantee of real improvement without having developed a real political alternative. The spectacle of continual outrage, furthermore, presents the danger that the Left will become stuck in oppositional and reactive mode, unable to impose its own agenda or to dictate the temporality of political developments.

2. Expanding the Social Composition

The primary means that I see to take the initiative and create a real social alternative is to expand the social basis of the movements. One of the most important and inspiring aspects of the Gezi encampment, in fact, was the way it opened the possibility for new political subjectivities and new articulations across the social spectrum. Rigid social divisions that previously seemed unbreachable suddenly seemed to dissolve among those together in the square. A year later, though, the openings have not (yet) been consolidated and even seem to have retreated.

Feminist and LGBT activists, for instance, gained widespread visibility at Gezi and were often cited as central to the movement. Some activists now, however, say that gender and sexuality equality remains a major problem in the movement and they even question whether the extent to which activists engaged feminist and LGBT issues and adopted their practices was exaggerated.

Another opening was provided by the presence in the Gezi encampment of the “anti-capitalist Muslims”, which confounded the standard narrative (vociferously reinforced by the AKP) that the primary social conflict can be posed strictly in religious versus secular terms. It was very easy, furthermore, for the group to wield Islamic doctrine and cite sacred texts to counter the neoliberal policies and corruption of the government. Despite the example of the “anti-capitalist Muslims,” the ideology of a secular / religious divide that corresponds to a global political division remains today a solid pillar used to support government power.

One of the potential connections opened at Gezi that is most significant, given the history of the Turkish Left, was that between Kemalist leftists (who have long abetted and even authored repression of the Kurds) and supporters of the Kurdish movement. A year ago I watched on Youtube a remarkable forum at the Gezi encampment in which a group of Kemalist activists apologized to Kurds for having believed what the media had said about them (and had failed to report) during the decades of government repression and atrocities. The media’s distortion of and failure to report the Gezi movement had taught them to read the past differently. The Kurdish movement was indeed present in the Gezi encampment, in its own corner, and there seemed possible a rapprochement to bridge a rift – perhaps the primary division – on the Turkish Left. One should keep in mind too that some sectors of the Kurdish movement were cool to the protests, in part because of the peace process in course with the AKP. My impression, though, is that the potential for a transformation of the Left regarding the Kurdish movement is real, although it appears to have advanced little in the past year.

Allow me to pause a moment to characterize briefly my understanding of the nature of the Kurdish movement – or movements, since Kurdish politics is by no means homogeneous – and its position on the Left in Turkey. Among some of the most dynamic, creative, and radical streams of the Turkish Left support of the Kurds is the fundamental basis of their political orientation. Key to the current situation, as I understand it, is the fact that roughly a decade ago the stream of the Kurdish movement that follows Abdullah Öcalan radically shifted strategy from armed struggle aimed at national sovereignty toward the development of “democratic autonomy” at a community level.

I find instructive a comparison proposed by several friends between the Kurdish movement and the Zapatistas. I can see a vague correspondence between the roles of Marcos and Öcalan, who is a kind of shadow leader that from prison periodically delivers somewhat poetic pronouncements that are interpreted by followers. The substantial and important point of contact, though, is the experimentation in village communities to practice a new kind of democracy. My limited knowledge makes it difficult for me to evaluate exactly what democratic autonomy means in practice as well as the depth and novelty of the experience in Kurdistan, but I’m convinced this is a rich and significant experience.

At this point the limits of the analogy with the EZLN become instructive for me. First of all, why do I know so little about the contemporary Kurdish experiments in democratic autonomy? I have a relatively deep knowledge of the thought and practice of the Zapatistas – beginning on 1 January 1994. And I’m not the only one. An entire generation of activists across the globe has oriented its political compass toward Chiapas. Why has so little international attention been focused on the Turkish Kurds? Surely the difference is not due only to the remarkable Zapatista facility with communication, Marco’s rhetorical brilliance, or more widespread linguistic facility with Spanish. It might be useful, in other words, to read my relative ignorance of Kurdish political developments not only as a personal failing but also as a symptom of a larger phenomenon.

A more significant question – but here I’m on much less solid ground in terms of my understanding – regards the political orientation of the non-Kurdish Turkish supporters of the Kurdish movement. Clearly there is a deep solidarity, an insistence on an end to the decades of state massacres and repression of the Kurds, and a respect for what the Kurdish movement has achieved. Global Zapatista supporters, however, in addition to solidary and respect, have long emulated Zapatista practices, translating them to their own local circumstances in Mexico City, Barcelona, Padua, Austin, Texas, and elsewhere. Is it possible (or perhaps already happening in some way) similarly to emulate the Kurdish experience, either in Turkey or elsewhere? What would it be like, for instance, to institute democratic autonomy in a neighborhood of Istanbul, Ankara, or Izmir? Such experiments would give real substance to the analogy.

To close this long parenthesis, then, it seems clear that the Gezi movement (and the Turkish Left in general) cannot advance without somehow bridging the divide between the republican, nationalist position and the Kurdish movements. Such a bridge is one of the promises of Gezi that remains unfulfilled.

Finally, the composition of the Gezi encampment and the post-Gezi movement should be read in terms of labor. It is striking how uniformly Gezi militants describe the class position of those most active in the movement as “white collar” (beyaz yaka): urban, young, and highly educated, but often poorly paid and precariously employed. I interpret “white collar” here to refer to a cross between the alienated bureaucracy workers that C. Wright Mills named by the term in the 1950s and the newly emerged cognitariat. Activists commonly insist, for example, “we’re not middle class, we are workers – white collar workers.” A revealing reference of white collar life during the protests, repeated to me more than once, is the film “Fight Club”: a dual life, dressed for office work during the day and fighting the cops at night. One of the positive results of Gezi has certainly been to advance the understanding of contemporary class composition, reconsidering the nature of the working class in light of such newly expanding labor categories.

A clear obstacle to the advance and expansion of the Gezi movement, however, is its narrow class basis. The white collar workers have to find a way to articulate their struggles with those of the traditional segments of the working class and well as those of the urban and rural poor. Such articulations, of course, would require transformations of both sides: traditional trade unions, in other words, have to open their conception of the working class and alter their traditional practices but also the militant, urban white collar workers have to modify some of their cultural assumptions and political orientations to make a productive articulation possible.

In this light, the Soma mine disaster struck me as an opportunity. The Gezi spirit was immediately shifted to focus on the plight of miners, their scandalous labor conditions, and the neoliberal policies that have both promoted and made more dangerous the extractive industries. Students occupied Istanbul Technical University to demand it break ties with the company that operates the mine and buses of students tried to travel to Soma, despite police blockades to exclude “outside agitators.” It is certainly an opportunity but one that must confront numerous hurdles, including not only a powerful government repression and propaganda machine but also the relative lack of existing political and cultural ties among different sectors of the contemporary working class.

My primary point here is that an essential challenge facing the Gezi movement one year after its emergence is to extend its social basis beyond the existing limits. By focusing on such obstacles I do not mean to suggest that Turkish activists are someone behind the other movements active in the current cycle of struggles. On the contrary, revealing and confronting these challenges are indicative of what has been achieved in Turkey. Since its inception, as I said, the Gezi movement promised a radically expansive social articulation, even though in many respects that seems to have stalled or run up against obstacles. Gezi raised the prospect of overcoming divisions across all the axes I have recognized: gender and sexuality, the religious / secular divide, the Kurdish question, and composition of labor – and there are undoubtedly others.

My primary point here is that an essential challenge facing the Gezi movement one year after its emergence is to extend its social basis beyond the existing limits. By focusing on such obstacles I do not mean to suggest that Turkish activists are someone behind the other movements active in the current cycle of struggles. On the contrary, revealing and confronting these challenges are indicative of what has been achieved in Turkey. Since its inception, as I said, the Gezi movement promised a radically expansive social articulation, even though in many respects that seems to have stalled or run up against obstacles. Gezi raised the prospect of overcoming divisions across all the axes I have recognized: gender and sexuality, the religious / secular divide, the Kurdish question, and composition of labor – and there are undoubtedly others.

Such a social articulation that expands the social basis of the movement is the only means, it seems to me, to take the initiative from the government, control the agenda, and construct a real political alternative in Turkey. That would fulfill the hopes and desires that were launched in Gezi.

“I am grateful to Boğaziçi University for its generous support. A revised and longer version of this essay will be published as part of the Boğaziçi Chronicles project.”