by PAVLOS HATZOPOULOS and DIMITRIS PARSANOGLOU.

1. The radicalisation of the Greek society exceeds all the formal social and political dynamics that have burst into the central political scene in the context of the two rounds of the Greek parliamentary elections (May 6 and June 17). The electoral results are overshadowed, in many respects, by the social forces and antagonisms that continue to push existing parliamentary politics to its limits.

The last gasp of the old political system was the attempt to strip off the electoral campaign from these antagonisms. The attempt has been ‘successful’, but only within the horizon of the short-term reduction of their electoral losses that seems impossible to sustain for much longer. In both elections, there was no political party campaigning with a pro-memorandum agenda (apart from some fringe neo-liberal parties, practically sponsored by media and corporate conglomerates, who didn’t even manage to reach the threshold of 3% of the votes in order to elect MPs). All the parties of the old establishment shifted towards a ‘re-negotiation of the memorandum’ platform that was supposed to neutralise the ‘politics of the nullification of the memorandum’ proposed by Syriza. The electoral dilemma was then set as one between ‘responsible multilateral negotiations’ with our European partners and a politics of unilateralism (that would automatically jeopardise Greece’s Euro membership according to the anti-Syriza bloc), but all within the framework of ‘the memorandum is not sustainable’ discourse. Along these lines, the ruling parties pursued a strategy of re-nationalisation, calling for national unity “to change the memorandum in the best we can”, and castigated Syriza for being the obstacle to the re-institution of this national unity.

Characteristically, in the political agreement of the three parties (Nea Dimokratia, PASOK, and Democratic Left) participating in the new coalition government, which has just been made public, there are practically no references to the implementation of memorandum policies. The text of the agreement reads as if the new government’s mandate is to simply nullify some of the existing austerity policies (such as the abolition of collective bargaining, the cut backs on the low pensions, and so on), couples with some general comments on economic development and the reform of the public sector.

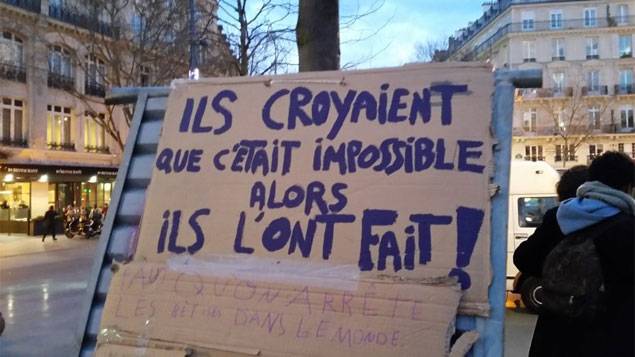

Even Syriza’s incomplete electoral success does not fully embody the radicalisation of the social attack against austerity policies. Syriza’s claim that, ‘regardless of what the result of the June 17 would be, the memorandum is null in practice’ could also be taken as a sort of critical self-reflection on its own secondary role and of the recognition of the primacy of social struggles. The politics of the nullification of the memorandum have exemplified the crisis, if not collapse, of representative politics, from trade unions to political organisations and parties. The social attack on austerity policies is based on the grassroots reorganisation of resistances through tools and actions that are assymetrical to representative politics: direct democratic procedures, non-hierarchical and non permanent structures, multiplicity, and most importantly, velocity of action. This ephemeral but direct response to challenges are grounded in everyday life for both ‘big’ and ‘small’ issues. From the response to the police shooting of 16 year-old student in December 2008 to the massive demonstrations against the austerity measures, from the organisation and networking of solidarities in order to gather and share foods and drugs for poor neighbours to reconnecting the electricity for people who could not pay the urgent tax for property paid through electricity bills. Occupations, liberations of public spaces, the movements of the squares, the local/neighbourhood assemblies are only some of the multiple forms of alternative or better subaltern modes of production of struggles.

In a nearly carnivalesque Syriza rally, involving speeches by Slavoj Zizek and Alexis Tsipras, Costas Douzinas made an introductory remark, asking, in a celebratory tone, Syriza to acknowledge its debt to the ‘movement of the squares’. ‘The multitude occupying the squares of Greece’, he continued, ‘will be transformed in June 17 to a people whose vote will bring Syriza to government’. Even if we take this remark, seriously, at least in terms of political rhetoric, Douzinas’ aim is more towards a ephemeral, momentary transformation: the multitude is to band to a people on the 17th and then immediately disband back to its previous multiplicity. The political success of Syriza is precisely based upon the fact that Syriza could not and did not attempt to represent the multitude that has invaded so persistently and so intensively the public space during the last years. In most of the struggles that have occurred the forces of Syriza, like most of the other organised forces of the left, apart from the Communist Party which constantly follows its own lonely path, could not but have a discrete presence without trying to pursue any hegemony of the movements. Even if domestic and international political, economic elites and media tried to present Syriza as the representative of the ‘dangerous political classes’, in practice the resistances or attacks are organised far beyond representative politics.

2. The radicalisation of the Greek society is multidirectional (including not only leftists and anarchists, but also nationalists and racists) This is exemplified by the rise of the neo-Nazi party, Golden Dawn, obtaining 7% of the votes in both elections of May and June.

The neo-Nazi far-right established itself at the very local level before gaining national visibility, building upon the politics of re-establishing order, as a form of “doing the work that the state or the elites cannot do” in the aftermath of the December 2008 revolt. Step by step, the far-right has conquered Aghios Panteleimonas, a neighbourhood that constitutes a paradox in the sense that it is a residential, historically working-class area, where social problems such as drugs and delinquency etc. are much less acute than in other areas, but became nevertheless a symbol of “reconquering/reoccupying our cities” (to use an expression repeatedly used by the new Prime Minister so beloved by all EU governments during the electoral campaign).

Apart from “de-filthing the place” (“Για να ξεβρωμίσει ο τόπος” was one of the slogans of the Golden Dawn), an endeavour that the fascists undertook in other districts, sometimes successfully like in Attiki square and sometimes unsuccessfully like in Amerikis square where they were pushed by anarchists of one of the oldest occupations that exist near the square, Lela Karagianni, and by the self-directed park of Kyprou and Patission street created by inhabitants in early 2009 against the plans of the Mayor to cut the trees and build a parking, the far-right activists have gradually implemented alternative informal welfare services and structures linked to the general sentiment of insecurity: accompanying old ladies when drawing money from ATM cash machines, intervening in migrant kindergartens, evicting migrants from squatted buildings and, of course, physically attacking brown and black people in the streets and in the metro.

We are referring to the methods employed by far-right groups in order to point out a qualitative shift that makes the confrontation of racism even more difficult. Usually, xenophobic, racist and nationalist political actors play in the field of ideology, trying to interplay with fear instincts and hateful pride. The main battlefield of far-right politics is that of ideology, where the main objective is to intersect their discourse with the structure of general feeling as Raymond Williams would have put it. Exactly the opposite has happened in Greece. The ideological legitimation of racism followed the spatial grounding/anchoring through every day practices, through a systematic implementation of what Gilles Deleuze called ‘micro-fascism’. In fact the ideological legitimation of the neo-Nazi agenda was made possible when the government, and particular two ministers, have intervened in the already polarised public discourse by announcing one month and a half before the elections of May the creation of 30 detention centres throughout the country and ‘zero tolerance’ measures against the “hygienic bomb that migrants, and particularly migrant women sex workers, constitute”.

3. After the result of the first round of Greek elections (May 6), it became clear that the second round would constitute the most Europeanised ‘national elections’ to date. The Europeanisation of the June 17 election has exemplified the limits of the politics of international solidarity. We don’t want to rest too much on the ‘politics of fear’ involved in this process of Europeanisation as they have been over-circulated by mainstream media as ‘news’ and by militant media in the form of critique (the proliferation of interventions/campaigning by European and political and economic elites aiming to prevent Syriza’s electoral win at any cost).

On the day when the talks for forming a government broke down after the May elections, Alexis Tsipras stated that the new elections can become the breaking point for a ‘Europeanisation from below’, claiming that the new elections can become the stage for a pan-European social attack against austerity. He immediately backed up these statements, by making trips to Paris and Berlin and sending a letter to the European Commission explaining his case.

As far as the Greek elections are concerned, the call for a ‘Europeanisation from below’ against austerity was translated in rather formalistic terms. Formal meetings of leaders that happened (Tsipras-Mélenchon) or that were refused (Tsipras-Hollande). Some statements of support for Syriza by homologous Left parties across Europe. And an impressive mobilisation of activist -mainly radical intellectual- networks across Europe expressing solidarity, support, and possibly making the case for the need of strengthening transnational networking and mobilisations. Clearly, however, this was not a constitutive moment of construction of such a movement.

Still, Tsipras’ statement is valuable, through its internal contradictions. It poses the problem of how to organise the constituent movement towards a ‘Europeanisation from below’ beyond the horizon of representative politics.