by BEPPE CACCIA, SANDRO MEZZADRA.

Preliminary notes on political methods of transformation.

On September 1st, at the closing of what was meant as our contribution to the ongoing debate, we wrote: “Under the sky of Interregnum, the horizon remains open”. In less than one week’s time, the unexpected developments of the “European refugees crisis” provided an amazing instance of such openness. The migrant subjectivity, bursting into the Continental stage (initially along the Balkan route, breaking all barriers in Macedonia and Hungary and then being carried forward by the Marches of Hope), has practically overcome all borders, dramatically re-orienting the public discourse surrounding refugees and migrants, and challenging Europe’s fierce and stupid migration and asylum policies. This strong pressure – both from the South and from below – has (re)activated (mainly in Central and Northern Europe) a widespread social fabric, characterized both by the active efforts of solidarity and by the ability to counter current narratives and racism’s odious practices, be they institutional or otherwise. It is undoubtedly a promising start: building power within the crisis must be seen as a process aiming at the construction of an alternative to the present state of things, and as such it inevitably and crucially requires an attempt to combine the strength of egalitarian struggles against austerity with the fraternity-inspired struggle to overcome borders. And a materialistic method means precisely to start from very real social dynamics and from real social subjects, in the flesh. Forward!

The Greece-charged month of July is well past us now, with its thrilling OXI victory at the July 5th referendum and the infamous “agreement” which came one week later. And yet Greece is still in the spotlight, not only because of its role in the ongoing debate within the international “left”, but also because of the scenarios that were opened up by Tsipras’ stepping down, Syriza’ splitting up and by new elections being called in late September. These scenarios are complex ones, and what we see at stake here is Syriza’s own nature, the party’s internal democracy after the rise of the “Popular Unity” list, the political and electoral perspectives of this latter force, the relationships between movements and institutions in the new conjuncture. Reality’s contradictions are striking a particularly blatant chord here, and no self-consoling short-cut, no ideological remedy distilled from past categories and frameworks can be of any practical use. The aim of this paper, however, is not to address such issues and contradictions directly. We will rather attempt to formulate a few methodological requirements capable, in this phase and from the standpoint of a kind of politics that aims at the radical transformation of the present state of things, to The expression is to help us get our bearings for evaluating the Greek situation and, inevitably, the European one that is mirrored in it.

We have used the words “in this phase”: we mean a phase which is still marked by recession and by an uncertain transition, both in Europe and in the World. Recently, many people have proposed the Gramscian category of “Interregnum” as suitable to describe some features of our present reality. Gramsci famously wrote that “a great variety of morbid symptoms appear” during the Interregnum, taken to mean a crisis situation, where “the old is dying and the new cannot be born”. And it is true, in fact: under many respects this definition, outlined in the aftermath of the Great Depression, is still valid: the organic crisis, in Gramsci’s view, was essentially a “crisis of hegemony”, and came about when the masses drifted away from “traditional ideologies” and the “ruling classes” became incapable of exercising a “leading” function, substituting it with a sheer exercise of coercion and “domination”. Doesn’t this sound parallel to the evident legitimation crisis of neoliberalism – both in Europe and elsewhere – and to the arrogance with which the “ruling classes” reaffirm their “rationality”? Gramsci clearly did not rule out the possibility of the Interregnum ending with the “restauration of the old” and yet, while examining the “organic crisis” during his solitary confinement in the Turi prison, he highlighted its features of unpredictability, openness, suspension.

On the one hand, therefore, the current European situation bears a sinister resemblance with the Thirties (suffice it to think of some aspects in the “refugee crisis”), but on the other hand enormous differences stand out. First of all, the global framework of the processes of valorization and accumulation of capital has deeply changed, multiplying and amplifying the unpredictable nature, openness and suspension of the crisis that we were mentioning. You probably remember how, in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, many people were saying that the last largest “socialist” country, China, was saving capitalism (especially US capitalism) from disaster? The financial earthquake set in motion by the Shanghai Stock Exchange crash a few days back, and, more in general, the global circulation of the crisis set off by the bursting of the subprime mortgages bubble (even if along deeply heterogeneous paths and timings), shows a very different reality. On the one hand, it once again shows that interdependence, fragility and vulnerability affecting even the economies of countries being presented as the strongest ones (the US “locomotive”, Germany “world champion in exports”, the “irresistible rise” of Brics, and so on) is a structural feature. On the other hand, it brings out (even under the dark auguries of the recession hitting the most important “emerging country”) the deep changes that have occurred over the past few years in the relationships between the once clearly identifiable “centers” and “peripheries” of world capitalism.

Any analysis and any initiative regarding Europe must be placed in the context of this permanent crisis of world-scale capitalistic domination. The landmark issue of migrations and the wars threatening at Europe’s borders are here to remind us at every minute, just as the permanent, and permanently disregarded promise of a chimeric Continental “economic recovery”. But crisis is evident even where high levels of “growth” and “development” are still recorded. It might be interpreted as a form of capitalist accumulation par excellence, in the time of its accomplished financialization. A high degree of uncertainty and unpredictability, both in economic and social dynamics and in their articulation with institutional forms, appears as a distinctive character of our time. However, in the Interregnum, compasses inherited from bygone eras are of little use.

And even more corrosive is Marx’s irony on those who linger on “writing recipes […] for the cook-shops of the future.” We start from our present times. We start from the need to build power within the crisis, a (counter)power of the many exploited, that can effectively act in the transformation of our lives in the name of freedom and equality. What happened during the European Summer crisis has, in its brutality, clarified that the imbalances in social relationships of power, the raw class point of view that emerges from their dialectic, the crucial issue of huge inequalities and denials of freedom that follow are absolutely crucial.

Keeping this in mind, let us prepare ourselves collectively to define a method that (as the Greek etymology metà odòs, “through / path” reminds us) can only coincide with the identification (and if necessary with the violent opening) of paths where apparently there are none – or where you cannot find use for the old maps. To “cast aside the loose earth and sand, that I might reach the rock or the clay”, Descartes wrote while he was living in a different Interregnum: what matters is whatever leads you from the earth and sand to the rock and clay. The method allowing us to do that today is, indeed, a revolutionary method.

This path cannot be linear, as is easily seen from even a quick description of what today we might define as the temporal and spatial coordinates of political action. In terms of temporality, the long-term trends in transformation and reorganization of capitalism, long-analyzed, are confirmed in their planetary dimension, but are implemented within profoundly heterogeneous contexts, each time modifying and adapting themselves both to global “turbulences” and to local “variables”. The changes in the composition and nature of labor, the maturity of social cooperation, the pervasiveness of the financialization process, the relevance of debt as an individual and collective device of exploitation, the new forms of the articulation between capitalist command and political domination, the political role of money: these trends, to name but a few, have further developed in the years of crisis. But, if considered together, they do not deploy any linear path of “development” – among other things, because, as we have previously pointed out, development and crisis are so structurally interwoven. Waiting for the “full deployment” of these same trends would be vain, and so would be to believe that the political subject (class composition), that can overturn them in revolutionary terms, could derive from them like a new Minerva. And neither can we rely on the messianic register of “the event”: capital has proven to be a formidable machine for the metabolization of “events” and for their conversion into fuel for its valorization. The problem of building power within the crisis can be defined, from the methodological point of view, as the need to work within an essential temporal disconnection, i.e. combining construction and accumulation of force, on one hand, and opening towards the unexpected, the Unzeitgemässigkeit on the other. Here, if you want to talk about a “politics of the event”, you have to mean the attitude of “seizing the opportunity”, fitting into those time openings that, in the conflict and in the break, allow the leap forward and affirmation of a more favorable power relationship.

A similar argument can be made in terms of spatiality. The “variable geometry” of political practice, pointing to the radical transformation of the present state of things, is now imposed by the very forms in which capitalism is reorganized – even in Europe, where during the crisis years we have witnessed a real revolution of economic and political spaces. We have analyzed in depth elsewhere the permanent combination of “homogeneity” and “heterogeneity” at the global, continental, national and local scales. On one side, this means an ongoing and unresolved dialectic between standardization and homogenization processes, and on the other the need to bring into play economic and political, social and cultural, even “anthropological” differences between places and areas. And each of these scales, far from presenting itself as fixed and stable, is invested by specific factors of crisis: an essential methodological priority in the Interregnum is that of identifying these factors, investing borders and “junctions” between different scales with a practice of political rupture and alternative.

In this respect, going back to the seemingly reassuring size of national sovereignty or of “territory”, either by a mythological recovery of “monetary sovereignty” or through the exaltation of the alleged “micro-communitarian” alternative, is impossible. Both “solutions” are likely to be overwhelmed by the violence of processes that cut across, and synchronize, any spatial dimension or “scale”. So what is our option for Europe? However annoying it may be for us to repeat it, we need to remember that for us such an option does not coincide with the EU’s institutional dimension or with any kind of “Eurocentrism”. Instead, we are strongly in favor of trying to build a political space in which these processes can be effectively challenged: this is the condition also for making “locally” grown experiences of struggle and construction of an alternative expansive and enduring. We know – and we sorely tested it in recent months – that the balance of power is strongly unfavorable. There is an urgent need to work hard to change it.

Within these temporal and spatial coordinates, what matters is to develop a renewed materialistic and realistic approach to actual social dynamics and struggles, dismissing any “fetishism of identities.” In this respect, the relationship with political and institutional processes, which is never one-sided and that is established and guided (and conditioned) by social dynamics and struggles, becomes crucial. Seen in this light, both Greece and Spain are laboratories of extraordinary importance, and a realistic assessment of the balance of power in Europe should lead us to be cautious with binary pairs such as “win / lose” or “victory / defeat”, and with the rhetoric of “capitulation” or “betrayal” that is related to it, when we evaluate experiences such as the Greek one in recent months. Consistent with what we have written on the temporal and spatial coordinates of political method in the Interregnum, we think that the basic criterion should rather be the accumulation of strength to build processes of “counter-hegemonic” government. We are talking about processes that need to be developed within and against “really existing neoliberalism” – being aware that the latter cannot be gotten rid of by decree, or by building up a caricature of what once used to be called “socialism in one country”. What emerges here is the purely ideological (and often unbearably sectarian) character of the positions with which, in the more or less “extreme” and self-styled “Marxist” Left, the solution of all current problems is identified with the “Grexit” plan. Such a position reveals a lack of understanding of the fundamental features of contemporary capitalism (“the effective truth of the thing”, to quote Machiavelli), pursuing the “imaginary view” of a nation State that – once “conquered” – should be the basic and fundamental actor for its transformation. Today, a politically radical position can only start – one more time – from the primacy of struggles. We must realistically acknowledge the limits that collide with the action of any government, and we must try to think and act out in new and original forms the dialectic between social struggles and government action.

Neoliberalism is neither simply an “ideology” nor a mere set of macro-economic policies: it is a “rationality” which has profoundly transformed the forms and subjects of economic and social action, as well as “public” institutions themselves, insofar as neoliberalism implements some basic features of contemporary capitalism. Whether this is done from a “reformist” or from a “revolutionary” perspective is not the point here – and anyway the validity of these categories currently needs to be tested and updated against the background of the temporal coordinates sketched above: in any case, to fight against neoliberalism involves taking at least a medium-term perspective. And it requires thinking and acting politically, far beyond the depletion of traditional representative politics. Of course, specific elections can play an extremely important role, but one thing has left the scene for good, and that is the basic time-framework of political representation, i.e. the proxy that is given to the government and that deflates politics between one election and the next. The Greek case showed it very well: the government action was dynamic and “powerful” whenever it managed to interact with the self-organized proliferation of a mutualistic social fabric, of multifarious practices of solidarity and struggle, and when it urged – without being able to represent it – the referendum. This is a key point, and we should keep it in mind for the future.

This raises the question of a profound renewal in the very notion of government – and, in particular, as we briefly mentioned above, in the relationship between government and struggles, movements, processes of mobilization, autonomous institutions of counter-power. It means, again, understanding what level in the exercise of power can challenge neoliberal policies and the dominant paradigm of austerity, which resulted in a permanent crisis management in Europe. Here binary pairs such as “parties / movements” and “institutional / anti-institutional”, pairs that are so easily moulded into “alliances” or “antagonism” to fit different contexts, really do not work any longer – neither in theory, nor in practice. The global and elusive, fluid and pervasive dimension of financial capitalism, the dramatic imbalance in the given social power relationships, the multifactorial complexity of each policy-making process, especially if change-oriented, are radically questioning movements and institutions alike. Such issues force us to reflect, urgently and immediately, on how ineffective social movements can be when they act self-referentially, and on the “limits” of government action when it keeps within the boundaries of established institutions. These are key issues, which need to be addressed urgently and without relying on exasperated tactics.

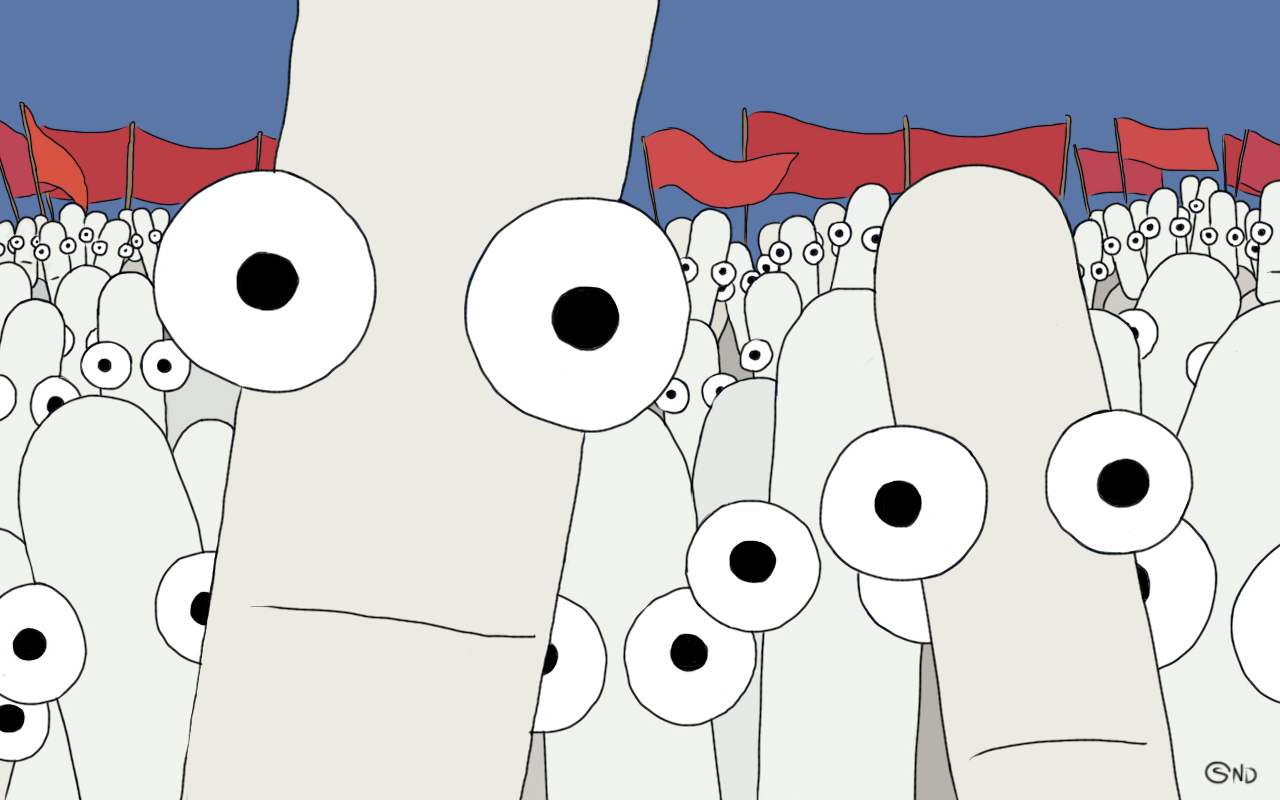

Even looking at the formidable experience of mutualism and social self-organization that has spread in Greece and elsewhere, what appears essential for us is to strive for a “social majority”, i.e. to reformulate the classic problem of the relationship between conflict and consensus. What is crucial is not so much measuring (through surveys and statistics) the impact of social conflicts on the production of “public opinion”, which is in itself a permanent battleground, but the political determination to build social majorities capable of making the construction of alternatives to the present state of things a realistic possibility. This is basically the lesson that we have drawn from reformulation of the category of “populism” by Podemos. Of course, we continue to criticize some theoretical assumptions: we believe that an excessive rigidity in its interpretation could easily escalate into national “sovereignism”; and we are convinced that drawing in around the party form, facilitated by “populism”, could create many problems, also in terms of electoral potential. Nevertheless, we recognize the strategic importance of re-opening a clear “majority” perspective. A subversive political methodology, in time of Interregnum, must necessarily be exercised on the field of political subjectivity, of its construction and its power: our “people” can only be “a people to come”, first of all in the sense that the political subject of transformation does not exist as yet. It is in its construction, in the necessary fight against the processes of corporatisation, social fragmentation, extreme individualization, which “really existing neoliberalism” incites and continues to nourish, that we need to retrieve and update the open and innovative character we have identified in the debates of the last few years around to the category of “multitude”. This must be done starting from the new and ambivalent relationship that is being determined (which can be determined) between singularities and collectivity. In any case, once again, building a political subject capable of being both radical and majority-oriented is today a key priority – to be pursued with any powerful tool, be it cultural or social, in the public opinion or election.

In terms of method, this process needs to be complex and articulated on multiple levels, from the very beginning. It must necessarily involve heterogeneous actors, engaged in different roles, taking charge of the problem of “synchronization” of different times, languages, behaviors, “cultures”, forms of social and political action that need to be as equally heterogeneous. The issue of coalitions emerges here as strategic, well beyond the daily political news and the perspectives of this or that specific “coalition”. At stake it is not the revival of a policy of “Popular Fronts” or “alliances”, but rather the discovery and construction of the political form that will be the appropriate tool (both as a political and an organizational project) for the practice of rupture and alternative, within the temporal and spatial coordinates we have tried to define. The coalition itself, in this sense, has to be a practice verified and continually reinvented beyond those binary oppositions (i.e. party / unions, movements / institutions) that present themselves as obstacles to the innovation we need if we want to revive a radically transformative politics. In the coming months we will measure the same activities of Left-wing parties – in Greece as in Spain but also in Italy, or Germany and UK – against the background of this coalition perspective, its naturally hybrid character, played on the border between social and political struggle, between institutional experimentation, mutualism and an integral federative approach.

What is at stake in the upcoming months is not how to solipsistically position ourselves in a completely ideological dispute, largely removed from our effective reach, – a dispute which is summarized in slogans such as “Yes to the Euro” or “No to the Euro ” (even though the monetary issue is and remains essential!) or “for a Left exit from the European Union” (yet we still consider crucial the issue of how to fight against the authoritarian mechanisms of EU governance on a transnational level!). What is at stake here is, rather, the decision on whether we want to be part – together with many others and at the very heart of social struggles – of a process of real change. Such a change is possible – and if it will be a real change it will necessarily turn also European governance and currency into fields of political struggle.

Let’s begin to hone our weapons, to forge the necessary tools for fighting these battles: under the sky of Interregnum, the horizon remains open.